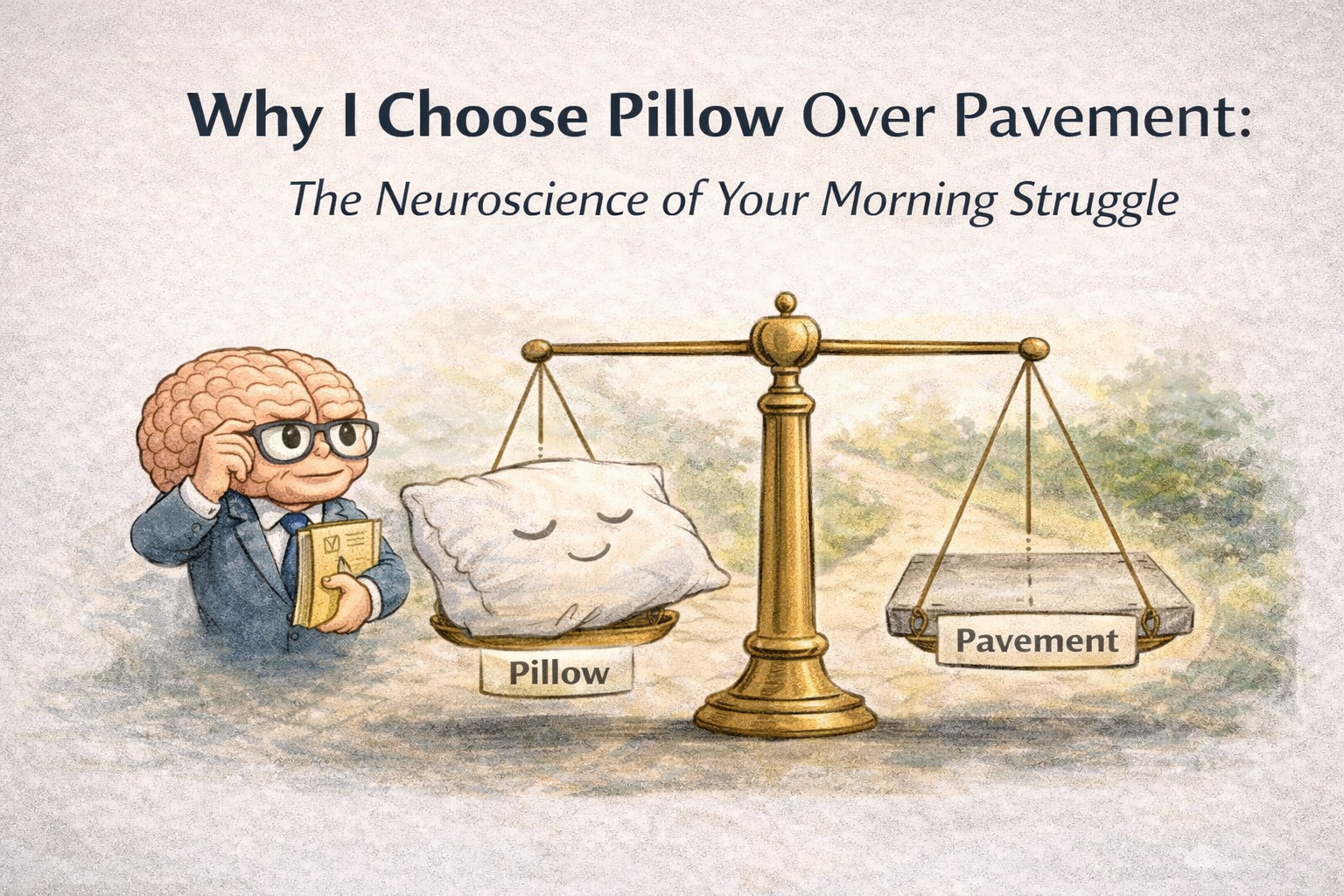

The alarm goes off. It’s 5:30 AM. You set it last night with the best intentions—today, you promised yourself, you’d finally go for that morning walk. You know it’s good for you. You know you’ll feel better afterward. You know your future self will thank you.

And yet, within three seconds of consciousness, your hand reaches out and hits snooze. The pillow wins. Again.

Why?

This isn’t about willpower. This isn’t about laziness. This is about a brilliantly designed brain making perfectly rational calculations—for a world that no longer exists.

Your Brain, The CFO

Neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett has revolutionized how we understand the brain. Forget everything you learned about the brain being primarily for thinking. That’s not its main job.

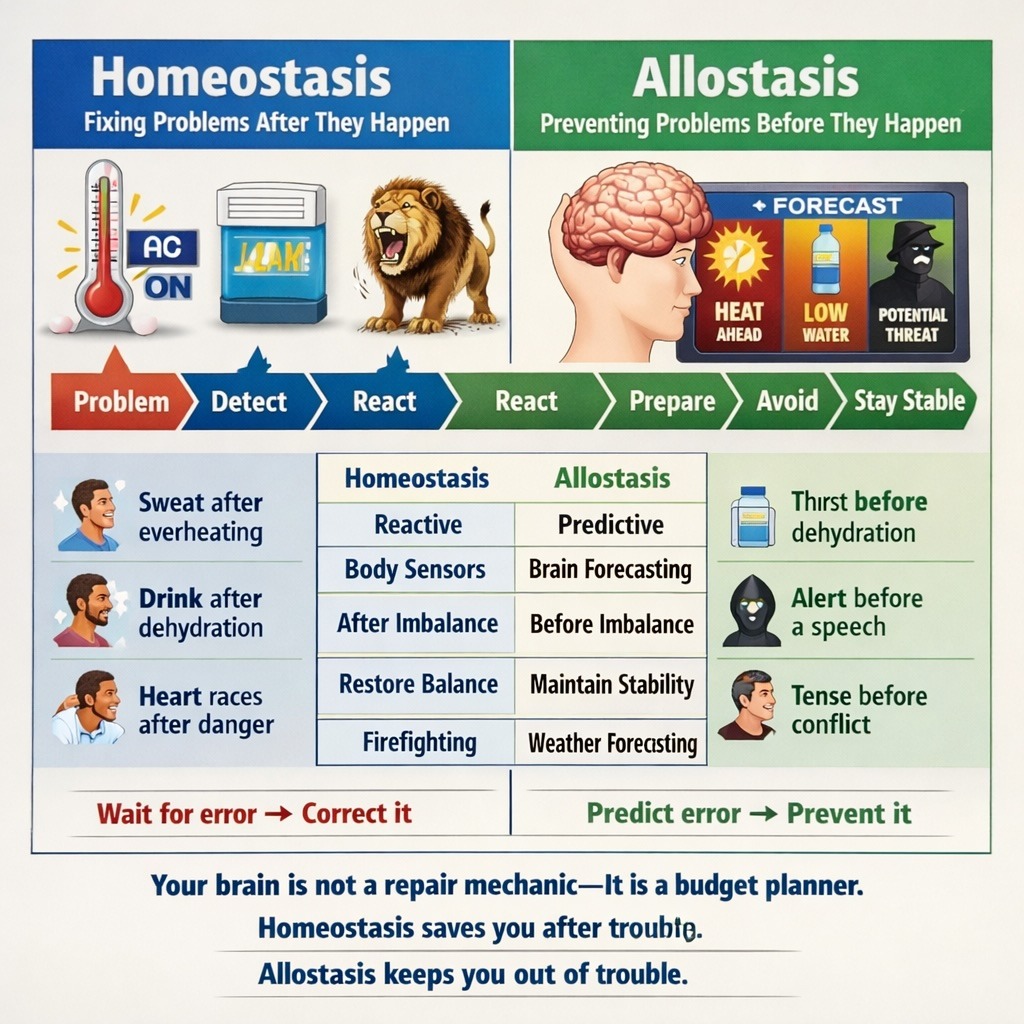

Your brain is the Chief Financial Officer of your body, constantly managing what Barrett calls your “body budget”—the energy resources needed to keep you alive and functioning. Every moment of every day, your brain is running calculations: What will this action cost? What will it gain? Should I spend energy here or conserve it there?

This budgeting system is called allostasis. Unlike homeostasis, which reacts to problems after they arise, allostasis is predictive. Your brain doesn’t wait until you’re dehydrated to make you thirsty—it anticipates your needs and triggers thirst before you run out of water. It doesn’t wait for danger to appear—it prepares your body for potential threats before they materialize.

This predictive ability was evolution’s gift to us. A creature that could prepare its movement before a predator struck was more likely to survive than a creature that waited for the pounce. Prediction beat reaction. This is why we’re here.

But here’s the problem: that same predictive system is now making decisions about whether you should walk or sleep, and it’s using accounting principles designed for life 100,000 years ago.

The 5:30 AM Calculation

When your alarm goes off, here’s what’s actually happening in your brain’s boardroom:

Immediate Costs of Getting Up:

- Energy expenditure to move cold muscles

- Thermal regulation cost (leaving warm bed for cold air)

- Metabolic activation required to transition from sleep to movement

- Glucose consumption for the walk itself

- Effort of overriding the powerful drowsiness signal

Immediate Benefits of Getting Up:

- None. Zero. Nothing your brain can detect right now.

Immediate Benefits of Staying in Bed:

- Continued energy conservation

- Maintained warmth

- Extended rest period

- No effort required

- Instant comfort

From your brain’s perspective as CFO, this is a no-brainer. Staying in bed preserves the body budget. Getting up depletes it. And remember—your brain’s primary job is managing this budget efficiently.

But wait, you might say. What about all those long-term benefits of walking? The improved cardiovascular health, the mood boost, the mental clarity, the weight management, the reduced disease risk?

Your brain knows about those. Your prefrontal cortex—the part of your brain that can think about the future—is well aware of these benefits. You read about them. You believe in them. You genuinely want them.

But here’s the brutal truth: that knowledge exists in a part of your brain that has almost no power at 5:30 AM.

Two Brains at War

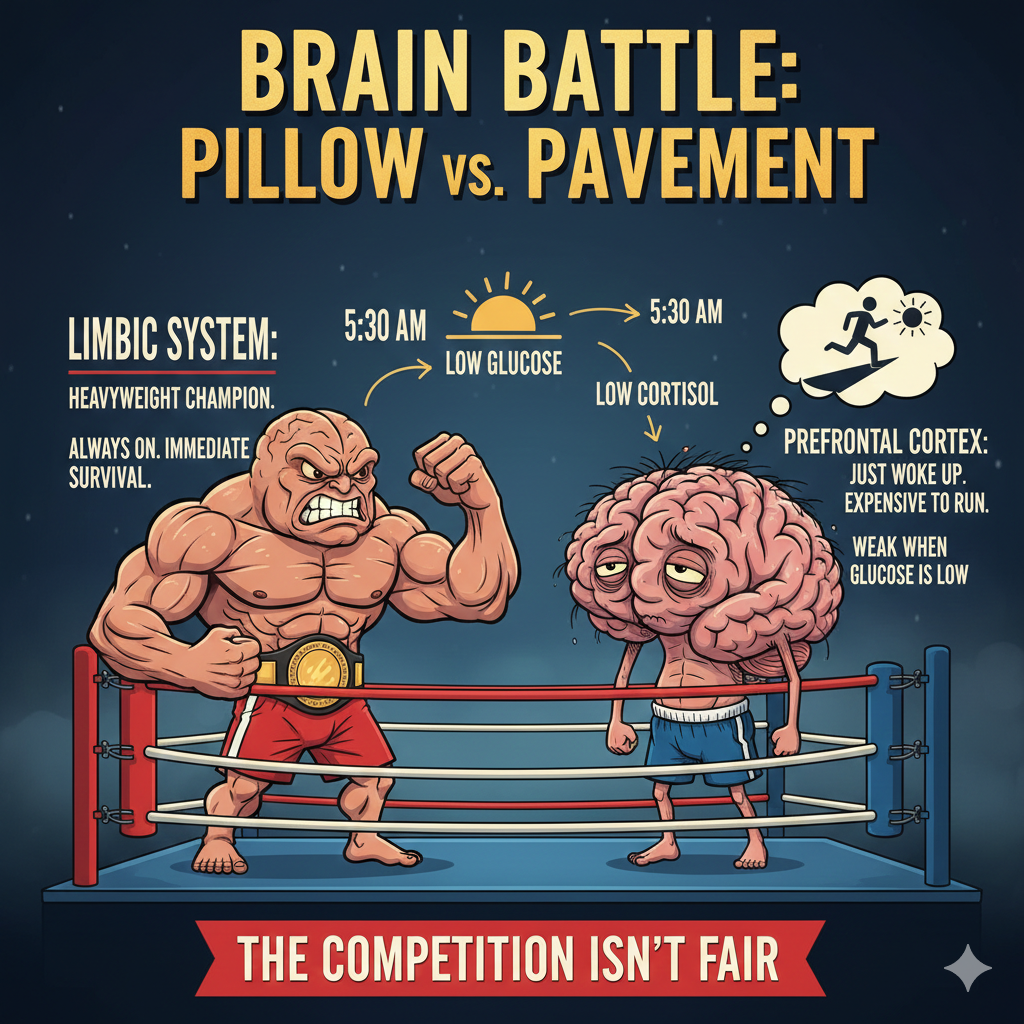

Brain imaging studies have revealed something fascinating: when you face a choice between an immediate reward and a delayed reward, two completely different neural systems activate, and they’re in conflict.

The limbic system—ancient, powerful, emotional—lights up for immediate rewards. This includes the ventral striatum, your brain’s pleasure and reward center. This system evolved hundreds of millions of years ago. It’s the same basic system a mouse uses, or a bird, or a lizard. It’s fast, automatic, and it doesn’t think about tomorrow. It thinks about right now.

When “stay in this warm bed” is available, your limbic system screams: “YES! This is exactly what we need! Conserve energy! Maintain comfort! This is survival!”

The prefrontal cortex—newer, more sophisticated, rational—activates for all choices, immediate or delayed. This is the part of your brain that can imagine future scenarios, that understands cause and effect across time, that can plan and deliberate. This is the part that knows the walk is better for you.

But here’s the problem: the prefrontal cortex is expensive to run. It consumes tremendous amounts of energy. And it’s at its weakest when your body budget is depleted—which it is after eight hours of sleep, before you’ve eaten, when your glucose levels are low, when your cortisol hasn’t fully kicked in yet.

Meanwhile, the limbic system is always on, always powerful, always focused on immediate survival and comfort.

The competition isn’t fair. It’s like putting a heavyweight champion (limbic system) in the ring with someone who just woke up and hasn’t had breakfast yet (prefrontal cortex). The outcome is predictable.

So the pillow wins. Not because you’re weak, but because the brain system advocating for the pillow is operating at full power while the system advocating for the pavement is running on empty.

The Evolutionary Logic: Why Your Brain Is Actually Right (Sort Of)

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Your brain isn’t making a mistake. From an evolutionary perspective, it’s making exactly the right call.

For more than 95% of human history—we’re talking hundreds of thousands of years—we lived in what researchers call an “immediate return environment.” When you made a decision, the consequences came quickly. You’re hungry? Hunt now, eat within hours. Problem solved. You’re cold? Find shelter now, get warm immediately. Threat appears? Run now, survive this moment.

In that world, conserving energy when no immediate demand existed was brilliant strategy. Resources were uncertain. Tomorrow might not come. The future was genuinely unpredictable—disease, predators, accidents, starvation, and violence made planning too far ahead often pointless.

In that environment, if you found food, you ate it. You didn’t save it for next week—it might spoil, or someone might steal it, or you might be dead. If you had the chance to rest, you rested. You didn’t say, “I’ll skip this rest so that decades from now I’ll have slightly better cardiovascular health.” That would be insane.

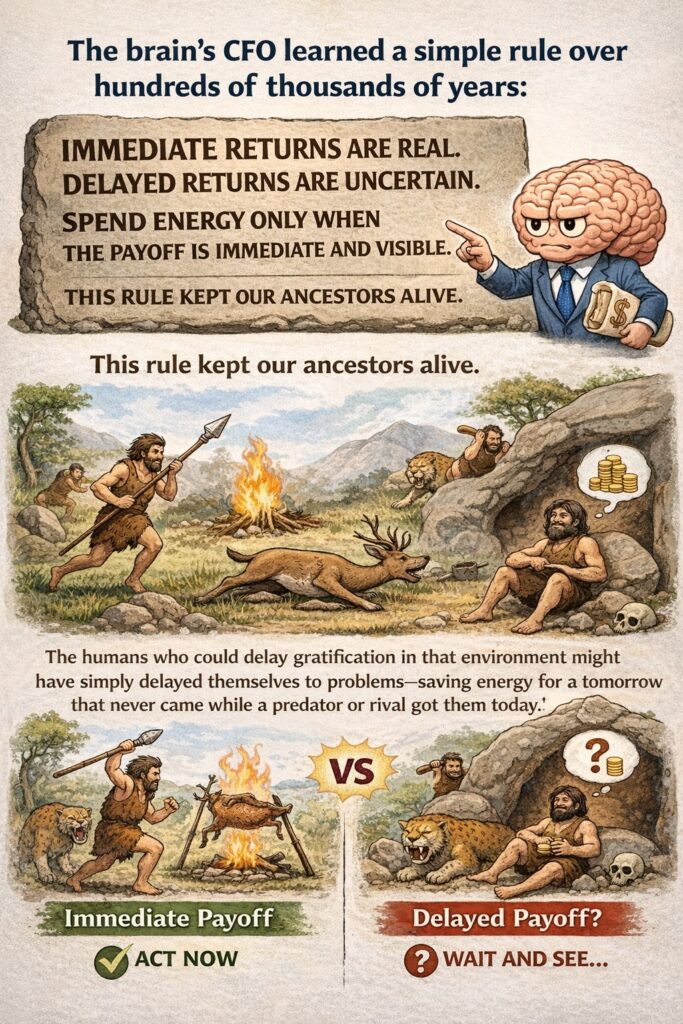

The brain’s CFO learned a simple rule over hundreds of thousands of years: immediate returns are real, delayed returns are uncertain. Spend energy only when the payoff is immediate and visible.

This rule kept our ancestors alive. The humans who could delay gratification in that environment might have simply delayed themselves to death—saving energy for a tomorrow that never came while a predator or rival got them today.

But then, in the blink of evolutionary time—really just the last 10,000 years, and especially the last 200—everything changed. We created what researchers call a “delayed return environment.”

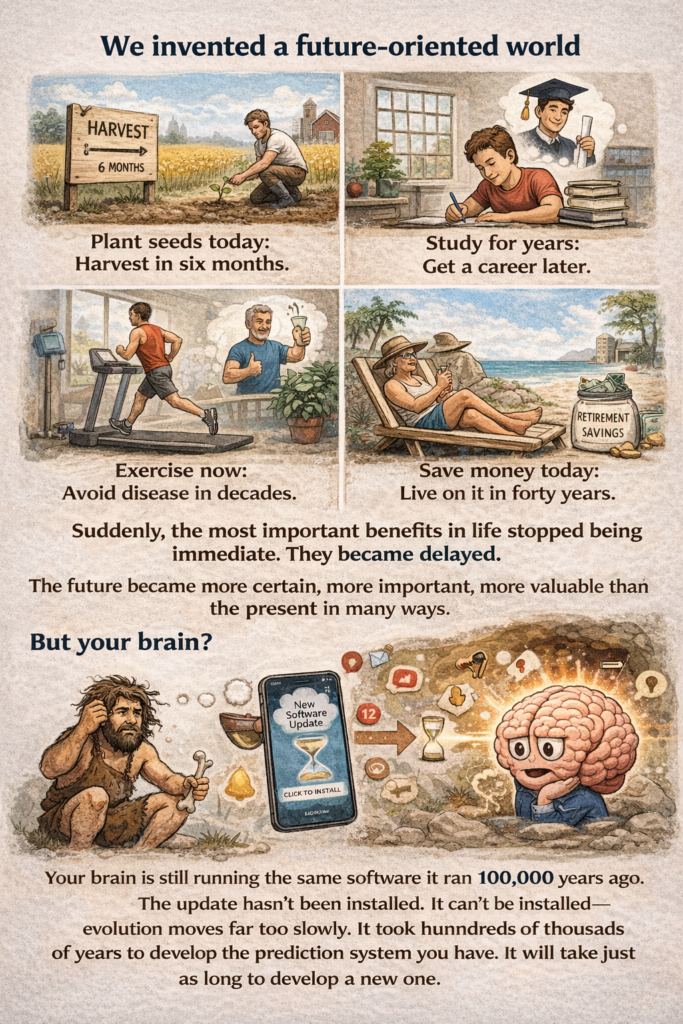

We invented agriculture: plant seeds today, harvest in six months. We created education: study for years, get a career later. We developed medicine: exercise now, avoid disease in decades. We built retirement systems: save money today, live on it in forty years.

Suddenly, the most important benefits in life stopped being immediate. They became delayed. The future became more certain, more important, more valuable than the present in many ways.

But your brain? Your brain is still running the same software it ran 100,000 years ago. The update hasn’t been installed. It can’t be installed—evolution moves far too slowly. It took hundreds of thousands of years to develop the prediction system you have. It will take just as long to develop a new one.

So when your alarm goes off at 5:30 AM, your brain makes a calculation using an algorithm designed for the African savanna: “Conserve energy unless there’s an immediate threat or opportunity.”

There’s no lion chasing you. There’s no visible food to gather. There’s just a vague promise that if you walk now, you’ll feel better later, be healthier eventually, live longer someday.

From your ancient CFO’s perspective, that’s not a compelling investment.

The Prediction Machine’s Fatal Flaw

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s research reveals another layer to this problem. Your brain doesn’t just react to what’s happening—it predicts what will happen and prepares your body accordingly. This prediction is what determines how you feel.

When you wake up, your brain makes predictions about what getting out of bed will cost and what it will gain. But here’s the flaw: these predictions are based on past experience, and they’re heavily weighted toward immediate costs versus delayed benefits.

Your brain remembers the immediate unpleasantness of leaving a warm bed. It remembers the effort of putting on shoes. It remembers the cold morning air. These are vivid, recent, immediate memories that feel real and certain.

The benefits of the walk? Those are abstract, distant, and uncertain from your brain’s perspective. Yes, you intellectually know you’ll feel better. But your brain’s prediction system doesn’t weight that knowledge heavily because it operates on felt experience, not intellectual understanding.

Here’s a cruel twist: the only way to update your brain’s predictions is through repeated experience. Your brain needs to learn, through doing the walk many times, that the benefits are real and worth the cost. But to do the walk many times, you need to override the current predictions. Which requires energy. Which your depleted morning body budget doesn’t have.

It’s a Catch-22 designed by evolution.

The Mental Simulation Trap

Humans developed the capacity for mental time travel—the ability to imagine futures that don’t exist yet. This was our superpower. It let us plan, prepare, and build civilization.

But in the morning, this same capacity becomes a problem. Your mind can simulate both futures:

Future 1: You stay in bed

- Immediate comfort continues

- Another hour of rest

- No struggle, no effort

- This simulation feels good right now

Future 2: You get up and walk

- Immediate discomfort

- Effort and cold

- Delayed benefits you can’t actually feel in the simulation

- This simulation feels bad right now

The irony is that you’re using a highly advanced cognitive ability (mental simulation) that evolved to help you make better long-term decisions, but that very simulation is corrupted by your ancient body budget system that values immediate returns over delayed ones.

You can imagine the future benefits of walking, but you can’t actually feel them in the present moment. Meanwhile, you can imagine—and almost physically feel—the immediate discomfort of getting up. The simulation itself is biased toward the immediate.

The Temporal Discounting Curve

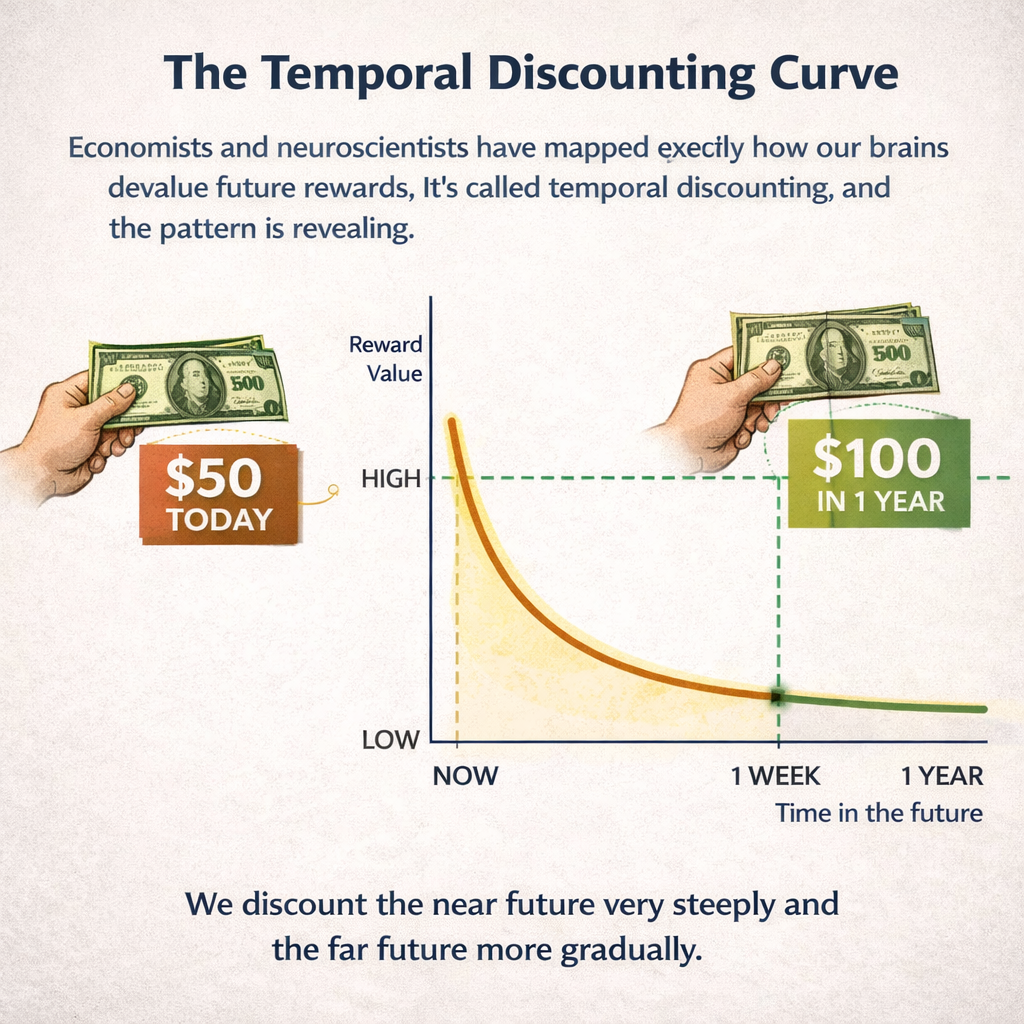

Economists and neuroscientists have mapped exactly how our brains devalue future rewards. It’s called temporal discounting, and the pattern is revealing.

Imagine you’re offered a choice: $50 today or $100 in a year. Most people take the $50, even though waiting would literally double their money. That’s temporal discounting—the tendency to assign lower value to future rewards simply because they’re in the future.

But the pattern isn’t linear. The difference between now and one week from now feels enormous. The difference between 52 weeks and 53 weeks? Barely noticeable. We discount the near future very steeply and the far future more gradually.

This makes perfect evolutionary sense. For our ancestors, near-term differences were life and death. Far-term differences were so uncertain they barely mattered—you might not be alive anyway.

When you’re lying in bed at 5:30 AM, your brain is applying this same discounting curve to the walk decision. The immediate comfort of staying in bed is valued at 100%. The benefits you’ll feel in four hours? Maybe 40%. The cardiovascular benefits you’ll accumulate over years? Your brain barely counts these at all in the moment.

The walk isn’t worthless to your brain—it’s just heavily discounted because it’s in the future. And in the equation of “immediate comfort versus discounted future benefit,” immediate comfort almost always wins.

The Modern Amplification

In our ancestors’ time, this battle between immediate and delayed gratification had natural boundaries. There weren’t that many immediately comfortable options. You could rest, yes, but you couldn’t scroll social media, watch streaming shows, or burrow deeper into a pocket-spring mattress with memory foam pillows.

The modern world has weaponized immediate gratification. We’ve engineered environments of unprecedented comfort and filled them with immediately rewarding activities. Your bedroom is temperature controlled. Your bed is scientifically designed for comfort. Your phone offers unlimited immediate entertainment within arm’s reach.

We’ve created a paradise for your limbic system and a nightmare for your prefrontal cortex.

Your ancestors might have faced a choice between “rest a bit longer” versus “go gather berries.” You face a choice between “stay in this perfectly temperature-controlled comfort chamber with infinite entertainment” versus “put on shoes and walk in the dark and cold for benefits you won’t feel for hours.”

The gap has widened. The ancient brain systems haven’t changed, but the modern environment has made immediate gratification more immediately gratifying and delayed gratification more distant than ever.

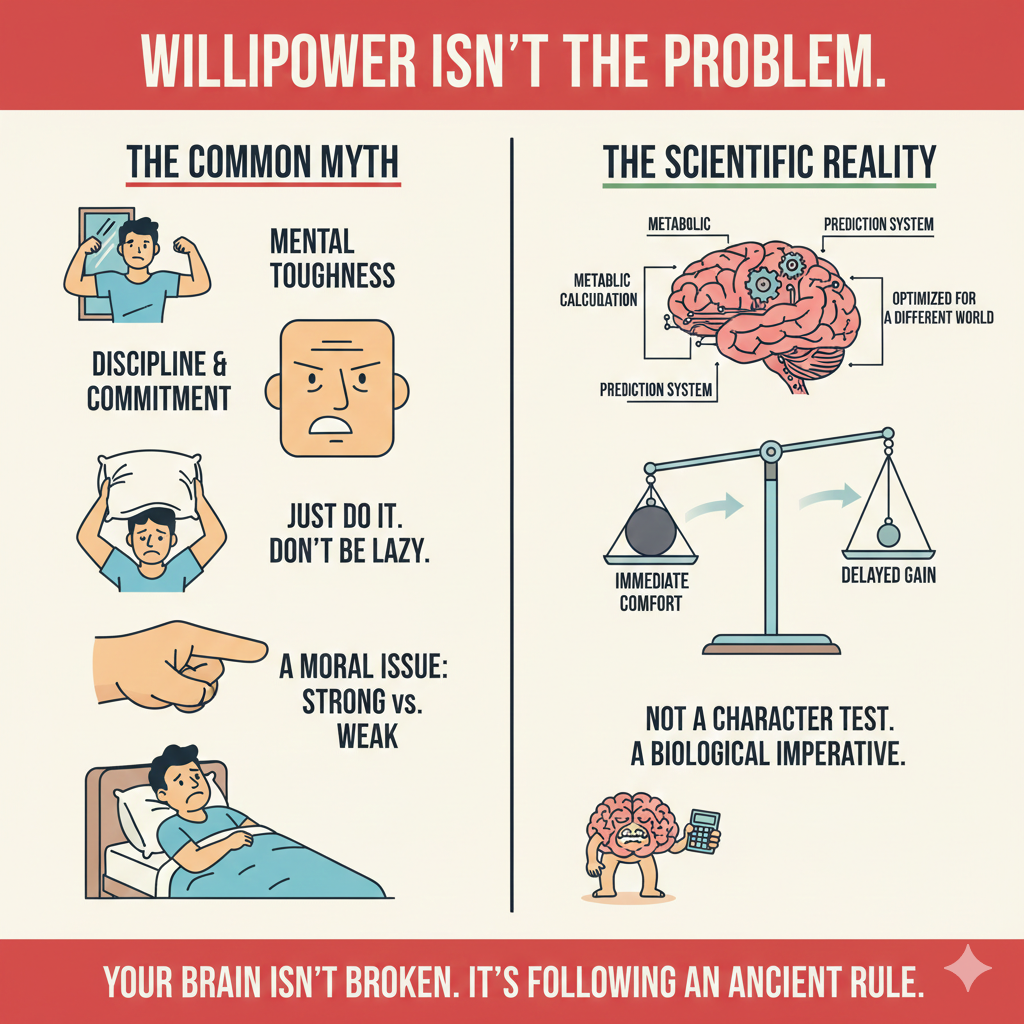

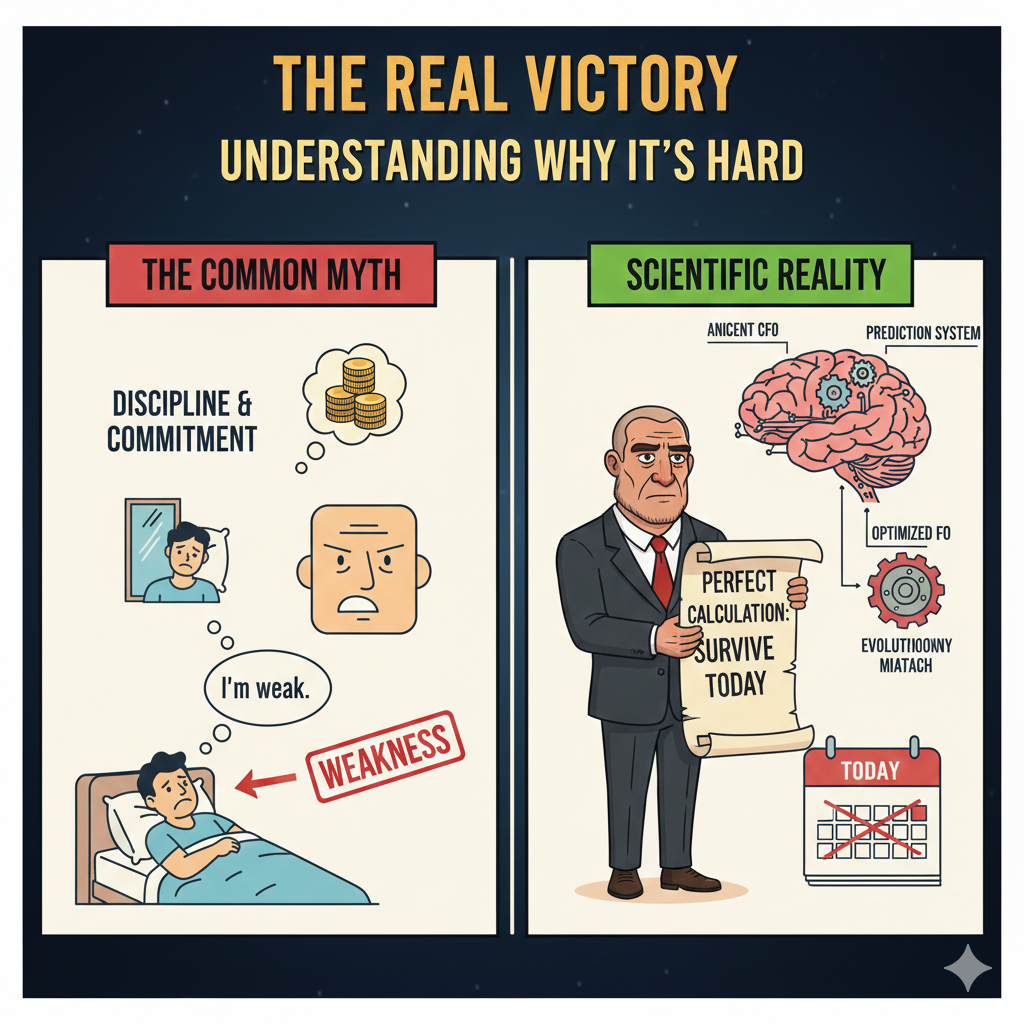

Why Willpower Isn’t the Answer

This is where most advice fails. People talk about willpower, discipline, commitment, mental toughness. They make it sound like a moral issue—strong people get up, weak people don’t.

But that’s not what’s happening. This isn’t a character test. This is a metabolic calculation made by a prediction system optimized for a different world.

Willpower is itself an energy expenditure. It costs something to override your brain’s automatic predictions. And when does your brain ask you to spend this energy? When your body budget is most depleted. Right when you wake up, before you’ve eaten, when your glucose is low, when your prefrontal cortex is barely online.

It’s like asking you to lift a heavy weight with tired muscles while simultaneously asking you to solve complex math problems. The system is designed to fail.

Relying on willpower is fighting evolution itself. Sometimes you’ll win. Most times you won’t. And every time you lose, you’ll feel like you’ve failed, which depletes your body budget further through stress and self-criticism, making tomorrow’s battle even harder.

The Way Forward: Tricking Your Ancient CFO

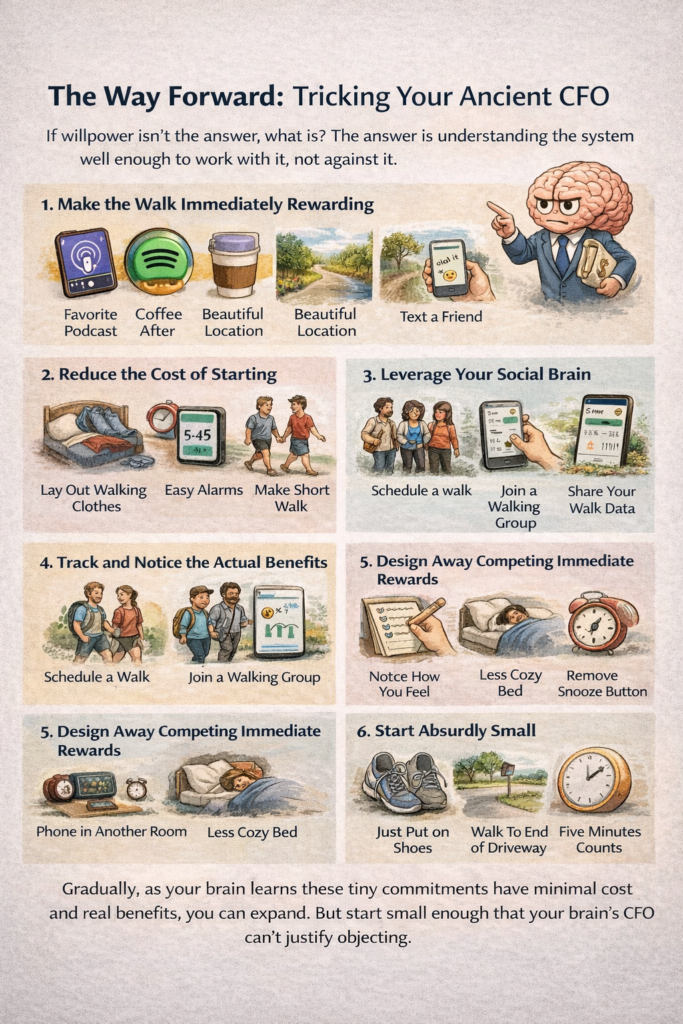

If willpower isn’t the answer, what is? The answer is understanding the system well enough to work with it, not against it.

Your brain’s CFO is making decisions based on predicted costs and benefits. So change the predictions. Change what counts as immediate. Change what the actual choice is.

1. Make the Walk Immediately Rewarding

Your brain needs immediate returns? Give them to your brain, but attach them to the walk.

- Reserve your favorite podcast exclusively for walks. Your brain gets immediate entertainment reward.

- Get coffee after the walk, not before. Your brain gets immediate caffeine reward.

- Walk somewhere beautiful. Your brain gets immediate sensory reward.

- Text a friend when you finish. Your brain gets immediate social recognition.

You’re not bribing yourself. You’re updating your brain’s prediction model to include immediate benefits in the “getting up” column of the ledger.

2. Reduce the Cost of Starting

Every step between thought and action is an energy cost your brain calculates. Reduce those steps.

- Put walking clothes next to bed. No decision needed, no searching required.

- Set multiple alarms with motivating messages. Reduce the mental effort of getting up.

- Make the walk short at first. Ten minutes counts. Your brain needs to learn the pattern is doable.

The easier you make the initiation, the less energy your brain predicts it will cost, the more likely you are to do it.

3. Leverage Your Social Brain

Your brain is exquisitely sensitive to social costs and benefits. Use this.

- Schedule walks with someone. The social cost of canceling creates an immediate negative consequence for staying in bed.

- Join a walking group. The immediate belonging and accountability shift the equation.

- Share your walk data. The immediate social recognition becomes a reward.

Humans are social creatures. Your brain weighs social factors heavily in its predictions. Make social factors support the behavior you want.

4. Track and Notice the Actual Benefits

Remember that your brain’s predictions are based on experience. You need to train it that the walk is worth it.

- Notice how you feel after walks. Explicitly observe the energy, mood, clarity.

- Write it down. Make it concrete enough that your brain can use it in future predictions.

- Compare days you walk to days you don’t. Let your brain learn the pattern.

You’re not just walking. You’re updating your prediction database. Each walk is data your brain will use tomorrow morning.

5. Design Away Competing Immediate Rewards

If your phone is next to your bed, you have an immediately available alternative reward (scrolling) that competes with the walk. Remove it.

- Phone in another room. Make scrolling require more effort than walking.

- Make bed less comfortable. Cooler room, lighter blankets. Reduce the immediate reward of staying.

- Remove snooze option. Make “get up” easier than “stay in bed.”

You’re creating friction for the behavior you don’t want and removing friction for the behavior you do want.

6. Start Absurdly Small

Your brain’s resistance is proportional to the predicted cost. Make the cost trivially small.

- Commit only to putting on shoes. That’s it. Once shoes are on, brain often follows through.

- Just walk to the end of the driveway. You’ve technically completed the commitment.

- Five minutes total. Laughably short, but it updates predictions without triggering resistance.

Gradually, as your brain learns these tiny commitments have minimal cost and real benefits, you can expand. But start small enough that your brain’s CFO can’t justify objecting.

The Deeper Understanding

Here’s what makes this struggle so fundamentally human: you are aware of it. You know the walk is better. You can imagine the future benefits. You understand the long-term consequences. You have all this advanced cognitive machinery that lets you think beyond the moment.

And yet, none of that is enough to override the basic body budget calculation made by an ancient prediction system.

This is the central paradox of modern human consciousness. We evolved the capacity to value the future, to delay gratification, to plan across years and decades. But we’re running this advanced software on hardware that’s still optimized for immediate survival in an unpredictable world.

The animal doesn’t face your struggle. The zebra doesn’t lie in the grass at sunrise thinking, “I should really get up and walk to build cardiovascular endurance.” It gets up when hungry, rests when not. No conflict, no guilt, no internal warfare.

You face this struggle precisely because you’re human, precisely because you have these competing brain systems, precisely because you can imagine futures and question your present choices.

The morning battle between pillow and pavement isn’t a bug in your system. It’s a feature of having a brain sophisticated enough to value long-term benefits but ancient enough to prioritize immediate survival.

The Real Victory

The real victory isn’t getting up every single morning. The real victory is understanding why it’s hard. Understanding that when you choose the pillow, you’re not weak—you’re experiencing an evolutionary mismatch. Your ancient CFO is doing its job perfectly; it’s just doing it in the wrong era.

This understanding doesn’t make getting up easier, but it does something perhaps more important: it removes the shame, the self-criticism, the sense of moral failure. You’re not losing a battle of willpower. You’re experiencing a perfectly predictable conflict between neural systems designed for different problems.

Some mornings you’ll override the ancient system. Some mornings it will win. The goal isn’t perfection. The goal is understanding the game well enough to gradually shift the odds in your favor by changing the rules, changing the rewards, changing the predictions.

Your brain is a brilliantly designed prediction machine, managing an incredibly complex body budget, doing exactly what millions of years of evolution trained it to do. It’s not your enemy. It’s not sabotaging you. It’s protecting you the only way it knows how.

The task isn’t to defeat it. The task is to work with it, to gently update its predictions, to teach it through experience that in this new world we’ve created, sometimes the pavement is better than the pillow—not because it feels better immediately, but because it makes the whole budget balance better over time.

And maybe, just maybe, after enough walks, after enough updated predictions, after enough experienced benefits, your brain’s CFO will revise its morning calculations. The pillow will still be comfortable. But the prediction for the pavement will include enough immediate rewards and recognized long-term benefits that the equation balances differently.

That’s when the walk stops being a battle and becomes simply what you do.

Until then, be patient with your ancient brain. It’s doing its best in a world it was never designed for. And every morning you manage to choose pavement over pillow, you’re not just taking a walk. You’re teaching an ancient prediction system new tricks, one step at a time.

The alarm will go off again tomorrow. The struggle will return. But now you understand why. And understanding, even if it doesn’t make the choice easier, makes the struggle make sense.

And sometimes, that’s exactly what we need.