Introduction

Have you ever wondered why the same situation can evoke completely different emotions in different people? Why does your heart racing feel like excitement before a presentation but anxiety before a medical test? The answer lies not in universal emotional fingerprints hardwired into our brains, but in a fascinating process of construction that happens every moment you’re alive.

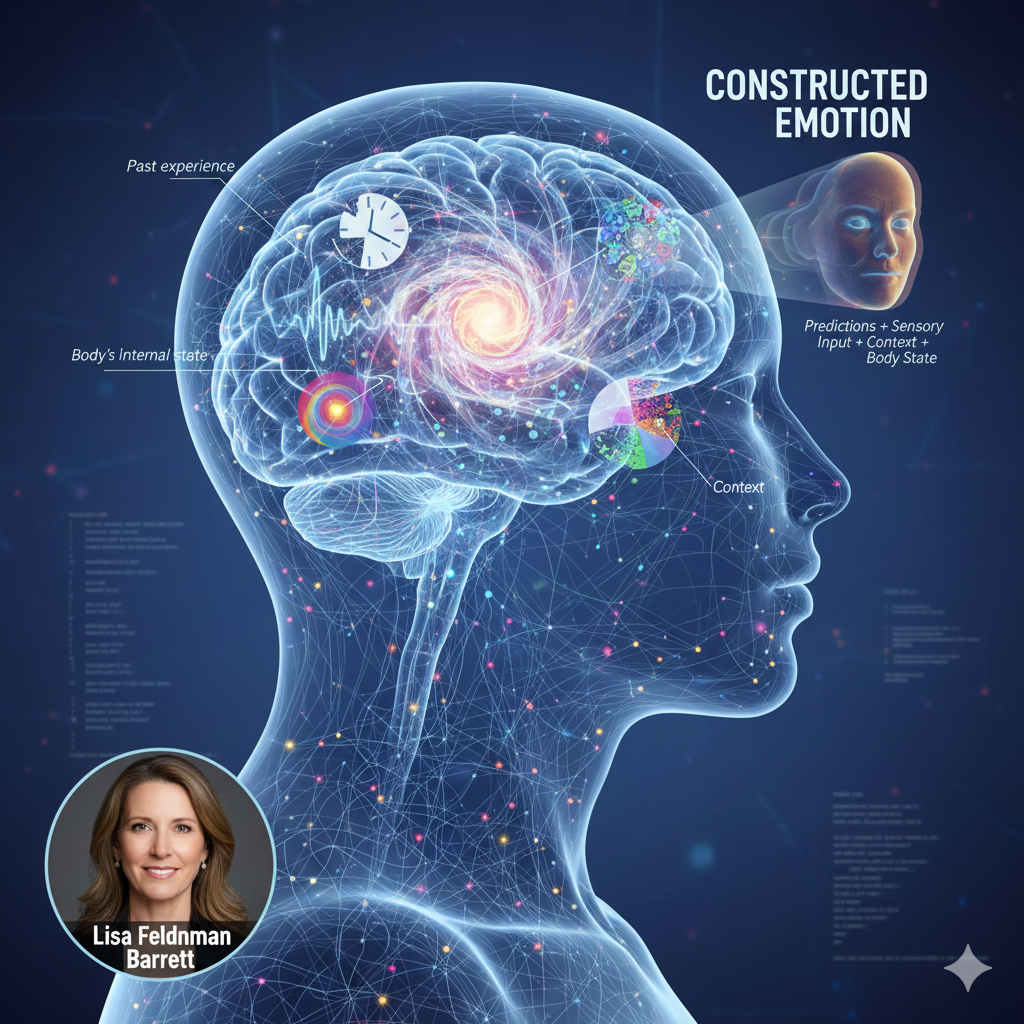

Neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett has revolutionized our understanding of emotions with her Theory of Constructed Emotion. Unlike the classical view that emotions are triggered reactions (like pressing an “anger button” in your brain), Barrett shows that emotions are constructed experiences – predictions your brain makes by combining sensory information with past experience, context, and your body’s internal state.

Let’s explore this journey from raw sensation to rich emotional experience.

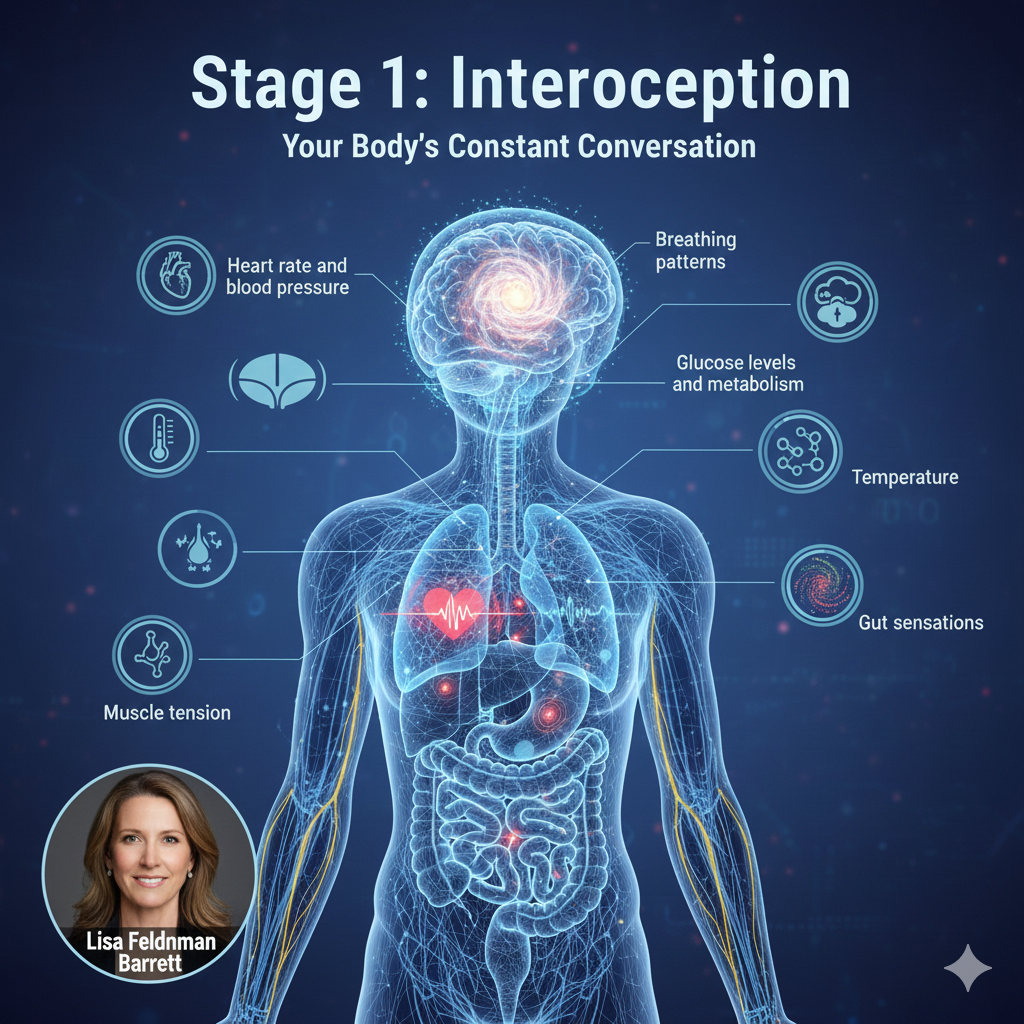

Stage 1: Interoception – Your Body’s Constant Conversation

Before you feel any emotion, something fundamental is always happening: your brain is monitoring your body’s internal state. This process is called interoception.

What Is Interoception?

Your brain constantly receives signals from inside your body:

- Heart rate and blood pressure

- Breathing patterns

- Glucose levels and metabolism

- Muscle tension

- Temperature

- Gut sensations

- Hormone levels

Think of interoception as your brain’s internal weather station, constantly checking conditions throughout your body. Most of this happens completely outside your conscious awareness – you don’t actively think about your blood sugar or heart rate, but your brain is tracking these signals continuously.

The Body Budget

Barrett introduces a crucial concept: your brain acts as the CFO of your body budget. Just like a financial budget tracks deposits and withdrawals, your body budget tracks energy resources:

- Deposits: Rest, nutrition, positive social interactions, sleep

- Withdrawals: Physical exertion, stress, illness, conflict

Your brain’s primary job isn’t thinking or feeling – it’s keeping you alive by managing this budget efficiently. Every action, thought, and emotion affects your body budget.

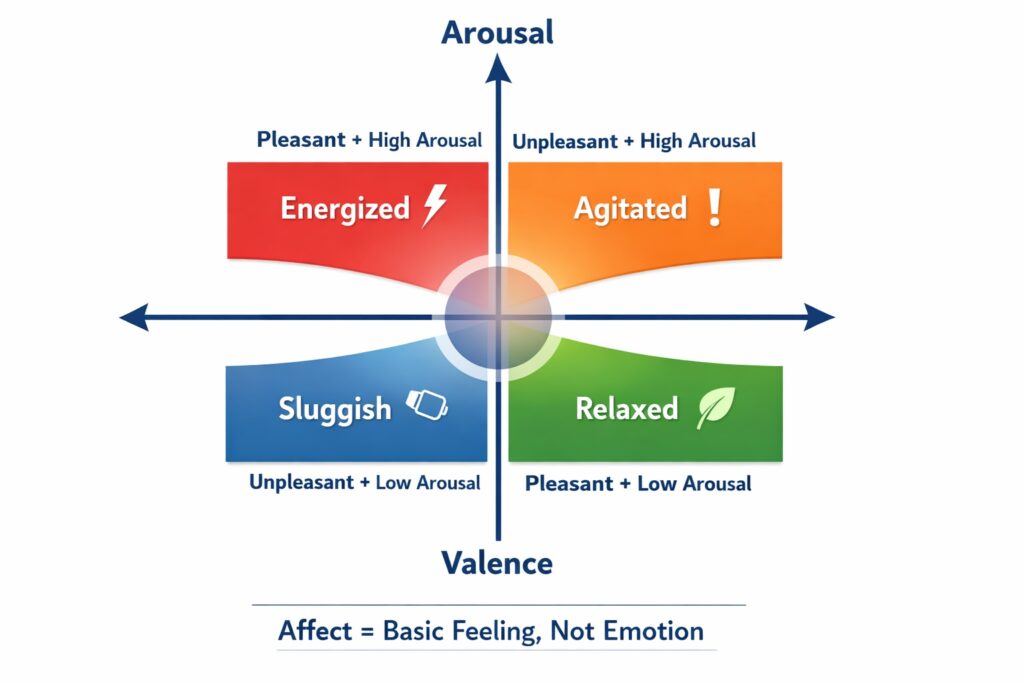

Stage 2: Affect – The Summary of Your Body State

From all those interoceptive signals, your brain creates a simple summary called affect (pronounced “A-fect”). Affect has just two dimensions:

1. Valence: Pleasant or Unpleasant?

Is your current body budget state feeling good (surplus) or bad (deficit)? This isn’t a thought – it’s a basic property of your consciousness, like brightness or loudness. You’re always somewhere on this pleasant-unpleasant continuum.

2. Arousal: Activated or Calm?

Is your nervous system revved up or quiet? High arousal means lots of activation (racing heart, heightened alertness). Low arousal means calm, restful states.

Important: Affect is not yet emotion. It’s a simpler, more basic feeling. You might experience:

- Pleasant + High arousal = energized, but not yet “joyful”

- Unpleasant + High arousal = agitated, but not yet “angry” or “anxious”

- Pleasant + Low arousal = calm, but not yet “content”

- Unpleasant + Low arousal = sluggish, but not yet “sad”

Affect is like the raw material that your brain will use to construct emotions.

Stage 3: External Sensory Input – The Outside World

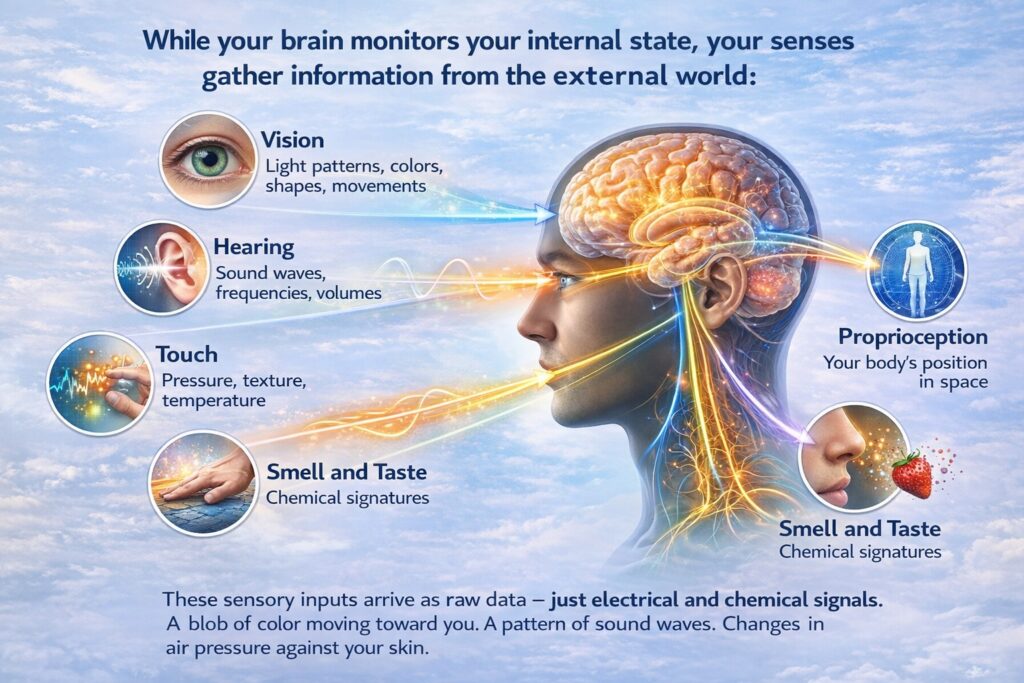

While your brain monitors your internal state, your senses gather information from the external world:

- Vision: Light patterns, colors, shapes, movements

- Hearing: Sound waves, frequencies, volumes

- Touch: Pressure, texture, temperature

- Smell and Taste: Chemical signatures

- Proprioception: Your body’s position in space

These sensory inputs arrive as raw data – just electrical and chemical signals. A blob of color moving toward you. A pattern of sound waves. Changes in air pressure against your skin.

Here’s the crucial point: These sensory signals don’t come pre-labeled with meaning. Your brain must figure out what they mean.

Stage 4: The Brain’s Predictive Engine

Now we reach the heart of Barrett’s theory. Your brain doesn’t passively wait for sensory information to arrive and then react. Instead, it constantly generates predictions about what’s happening and what will happen next.

How Prediction Works

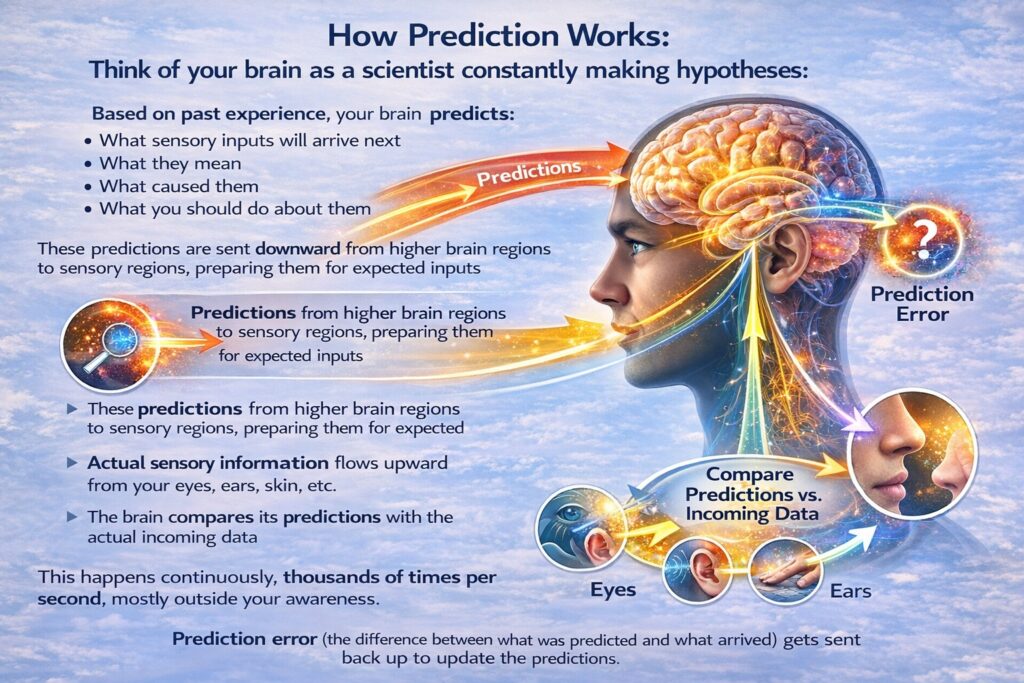

Think of your brain as a scientist constantly making hypotheses:

- Based on past experience, your brain predicts:

- What sensory inputs will arrive next

- What they mean

- What caused them

- What you should do about them

- These predictions are sent downward from higher brain regions to sensory regions, preparing them for expected inputs

- Actual sensory information flows upward from your eyes, ears, skin, etc.

- The brain compares its predictions with the actual incoming data

- Prediction error (the difference between what was predicted and what arrived) gets sent back up to update the predictions

This happens continuously, thousands of times per second, mostly outside your awareness.

Why Prediction Matters for Emotion

When your heart is racing and you’re breathing quickly (affect: unpleasant + high arousal), your brain asks: “What’s causing this body state? What does it mean?”

Your brain’s answer depends on context and past experience:

- Context: You’re at the gym → Prediction: “I’m exerting myself”

- Context: You’re giving a speech → Prediction: “I’m excited and ready”

- Context: You’re in a dark alley → Prediction: “I’m in danger – this is fear”

- Context: You’re meeting someone attractive → Prediction: “I’m attracted – this is nervous excitement”

Same physical state (racing heart, quick breathing), different emotions – because your brain made different predictions about the cause and meaning.

Stage 5: Categorization – Creating Emotional Experience

The final step is categorization – your brain sorts this combination of affect, sensory input, and predictions into an emotional category.

Emotion Words Are Concepts

Barrett’s revolutionary insight: Emotions are not universal, biological reflexes. They’re conceptual acts – your brain categorizing your experience using emotion concepts you’ve learned.

Just like you learned the concept “dog” by seeing many different examples (big dogs, small dogs, fluffy dogs, smooth dogs), you learned emotion concepts like “anger,” “joy,” or “anxiety” through experience in your culture.

The Construction Process

Here’s how your brain constructs an emotional experience:

- Situation occurs → Sensory input arrives (someone frowns at you)

- Body budget changes → Affect shifts (unpleasant + aroused)

- Brain predicts → “What situation is this? What does it mean?”

- Searches past experiences for similar patterns

- Considers current context

- Accesses emotion concepts available in your culture

- Brain categorizes → “This is anger” or “This is embarrassment” or “This is anxiety”

- Experience emerges → You feel angry (or embarrassed, or anxious)

- Action prepared → Your brain prepares appropriate responses (confront, hide, flee)

The Same Affect, Different Emotions

This is why the same body state can become different emotions:

Scenario: You’re alone in your apartment. You hear a loud crash from another room. Your heart races (affect: unpleasant + high arousal).

Prediction A: “A burglar broke in!” → Emotion: Fear → Action: Call police, find weapon, hide

Prediction B: “My cat knocked something over!” → Emotion: Annoyance → Action: Sigh, go check the damage

Prediction C: “The shelf I poorly installed finally collapsed!” → Emotion: Frustration (with yourself) → Action: Get tools to fix it

Same physical state, same sensory input (loud crash), but three different emotions because your brain made three different predictions about the cause.

The Brain’s Simulation

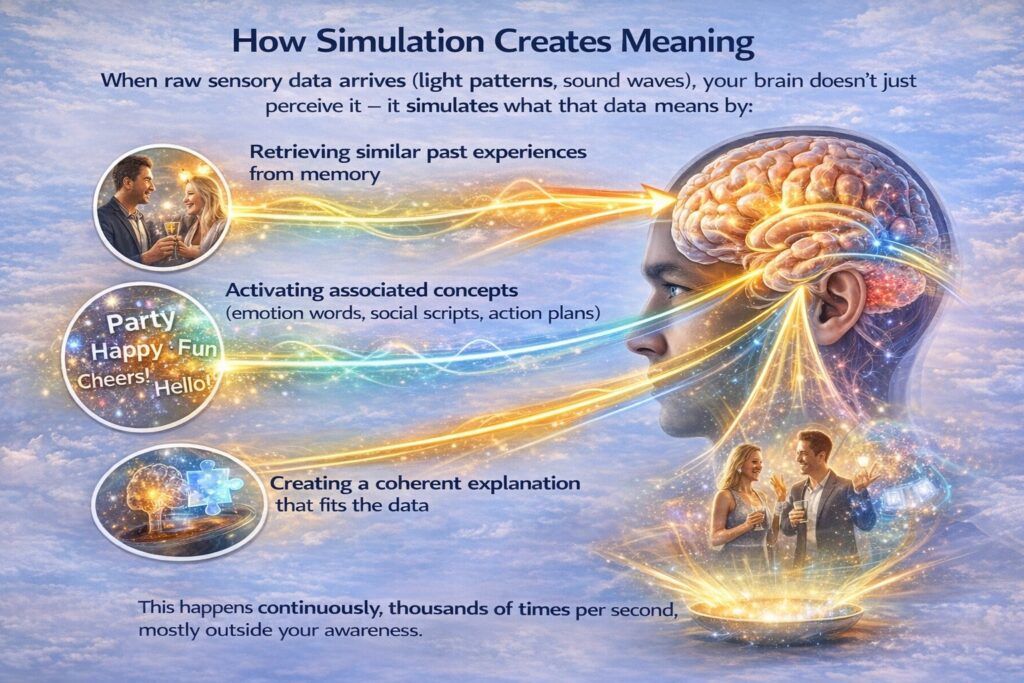

Barrett uses the term simulation to describe this process. Your brain is constantly simulating – running mental models of what’s happening based on past experience.

How Simulation Creates Meaning

When raw sensory data arrives (light patterns, sound waves), your brain doesn’t just perceive it – it simulates what that data means by:

- Retrieving similar past experiences from memory

- Activating associated concepts (emotion words, social scripts, action plans)

- Creating a coherent explanation that fits the data

For example, when you see a face:

- Raw data: Patterns of light and shadow, muscle configurations

- Brain simulation: “Furrowed brow, downturned mouth, tense jaw… in past experience, this predicted someone was angry… they’re standing close and speaking loudly… my body is tense…”

- Constructed meaning: “This person is angry at me”

- Emotional experience: You feel threatened or defensive

Predictions Become Reality

Here’s something profound: Your predictions shape what you perceive and feel. Your brain doesn’t wait to collect all the data and then react. It predicts first, and those predictions color your experience.

If you expect someone to be hostile, you’re more likely to:

- Notice hostile cues in their behavior

- Interpret ambiguous actions as hostile

- Feel defensive or angry

- Respond in ways that might actually provoke hostility

This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Summarization: Making Sense of Complexity

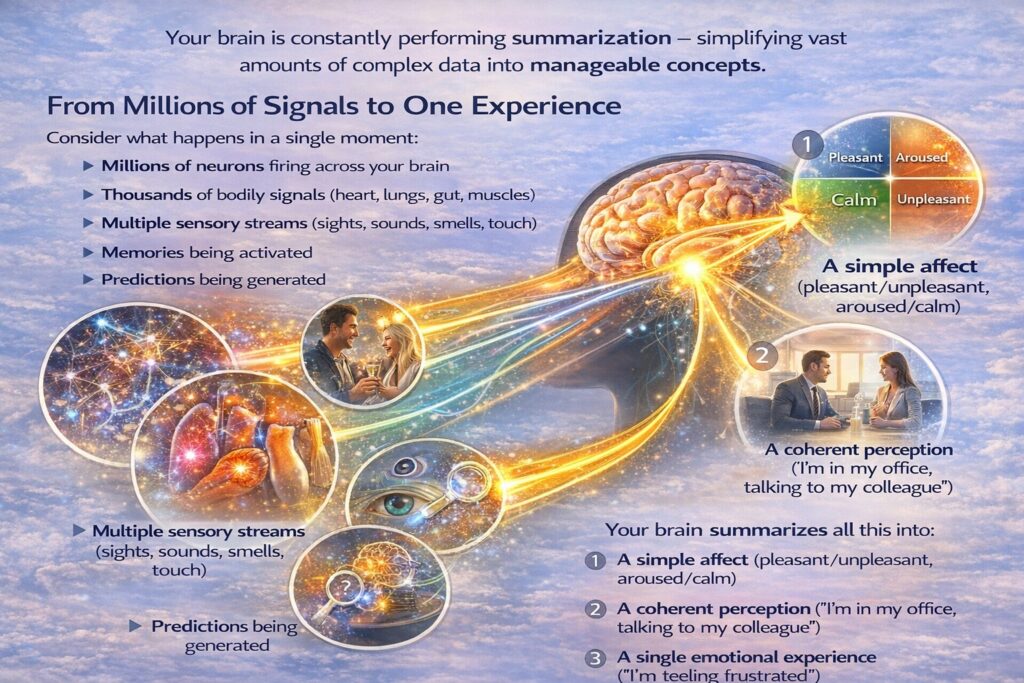

Your brain is constantly performing summarization – simplifying vast amounts of complex data into manageable concepts.

From Millions of Signals to One Experience

Consider what happens in a single moment:

- Millions of neurons firing across your brain

- Thousands of bodily signals (heart, lungs, gut, muscles)

- Multiple sensory streams (sights, sounds, smells, touch)

- Memories being activated

- Predictions being generated

Your brain summarizes all this into:

- A simple affect (pleasant/unpleasant, aroused/calm)

- A coherent perception (“I’m in my office, talking to my colleague”)

- A single emotional experience (“I’m feeling frustrated”)

This summarization is both necessary (you couldn’t function with raw, unsummarized data) and limiting (you miss the complexity of what’s actually happening).

Emotional Granularity

People differ in how finely they summarize their emotional experiences. Barrett calls this emotional granularity:

Low granularity: “I feel bad” or “I feel good” – broad, simple categories

High granularity: “I feel melancholic,” “irritated,” “disappointed but hopeful,” “nostalgic” – fine-grained distinctions

Higher emotional granularity gives your brain more precise predictions and more tailored responses. Instead of a blunt “I’m stressed” (which might trigger general anxiety), you might realize “I’m feeling overwhelmed by too many small tasks” (which suggests: delegate, prioritize, or batch similar tasks).

Implications: You Have More Control Than You Think

Understanding Barrett’s theory has profound implications:

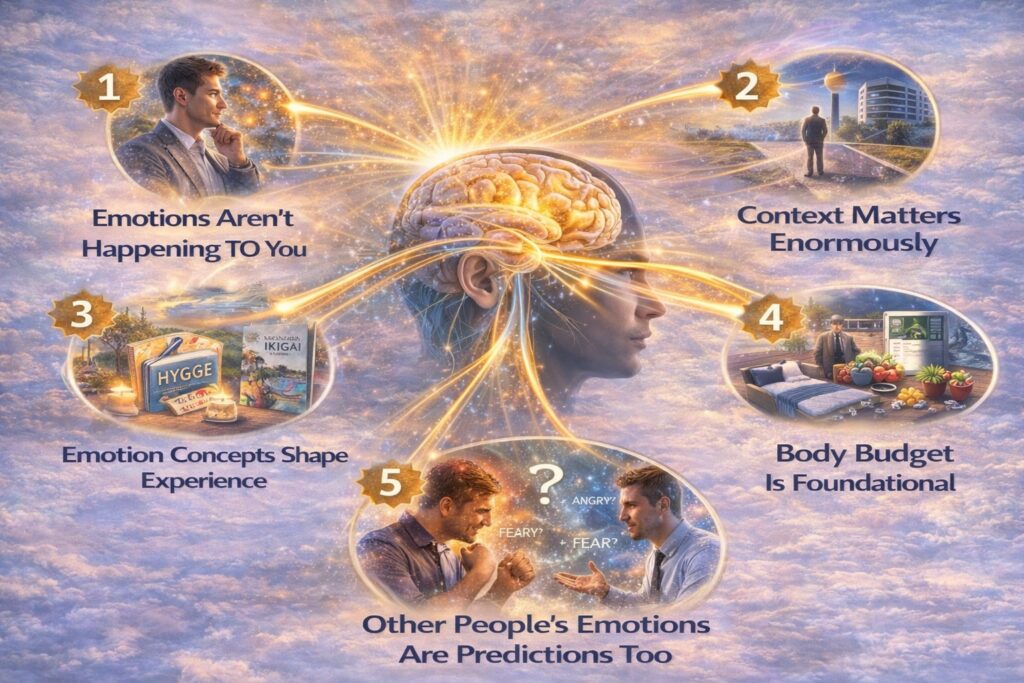

1. Emotions Aren’t Happening TO You

You’re not a passive victim of emotional reactions. Your brain is actively constructing your emotional experiences based on predictions. By changing your predictions (through new experiences, reframing, or emotion concept learning), you can change your emotions.

2. Context Matters Enormously

The same body state becomes different emotions in different contexts. Managing context – putting yourself in situations that promote helpful predictions – is emotion regulation.

3. Emotion Concepts Shape Experience

The emotion words and concepts available in your culture shape what you can feel. Learning new emotion concepts (like the Danish “hygge” or Japanese “ikigai”) literally expands your emotional repertoire.

4. Body Budget Is Foundational

Managing your body budget – through sleep, nutrition, exercise, stress management, and social connection – is the foundation of emotional well-being. When your body budget is depleted, your brain predicts threat more readily.

5. Other People’s Emotions Are Predictions Too

When you see someone as “angry,” you’re constructing their emotion through your predictions. They might actually be experiencing fear, frustration, or even excitement. This creates space for curiosity rather than certainty about others’ feelings.

Conclusion: The Constructive Nature of Experience

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s theory reveals that emotions aren’t universal, inevitable reactions hardwired into our biology. They’re sophisticated constructions – your brain’s best guess about what your body state means in the current context, based on a lifetime of experience.

The journey from sensation to emotion is a creative act:

- Interoception provides the raw material (body budget state)

- Affect summarizes it (pleasant/unpleasant, aroused/calm)

- Sensory input adds context (what’s happening around you)

- Prediction generates meaning (what does this mean? what caused it?)

- Categorization constructs experience (this is anger, joy, fear…)

Understanding this process doesn’t diminish the reality of your emotions – they’re completely real experiences. But it reveals their constructed nature, which means they can be reconstructed differently.

Your emotional life isn’t fixed. By changing your predictions, expanding your emotion concepts, managing your body budget, and cultivating awareness of the construction process itself, you can literally change what you feel.

You are not at the mercy of your emotions. You are, in a very real sense, their author.

Here is a youtube video to better understand her theory :